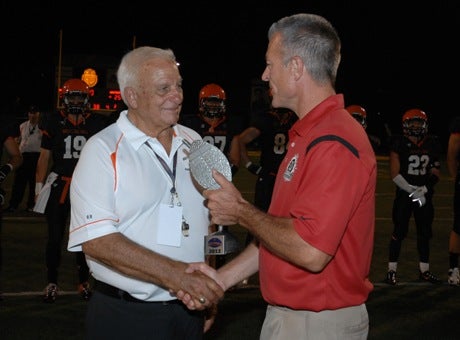

Brother Rice head coach Al Fracassa accepts the Prep Kickoff Classic trophy in 2012. The legend has announced that 2013 will be his final season.

File photo by Chris Fleck

Though his final season at

Brother Rice (Bloomfield Hills, Mich.) has not yet started, legendary football coach Al Fracassa already is fretting.

The 80-year-old marvel, who ranks No. 6 for coaching victories in high school football history with a 416-117-7 record, told MaxPreps, "I've been losing sleep watching film of

St. Ignatius (Cleveland, Ohio). We have 660 boys in grades 9-12; they have around 1400."

Fracassa's Warriors will open the 2013 season against perennial national power St. Ignatius on Aug. 31 at Wayne State University. Don't feel too sorry for him, though, because his two-time Division II defending state champions return six starters on both sides of the ball. Last season was Fracassa's ninth state title in 53 years of coaching.

He has sent more than 300 players to colleges, 13 of them to the NFL. One of them, now retired defensive tackle Mike Lodish, played in a record six Super Bowls.

Fracassa has received honors galore. In 1997 he was named NFL High School Coach of the Year. In 2002 he was named National Coach of the Year by the American Football Coaches Association. He's also garnered Michigan's Coach of the Year award four times and is a member of the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame.

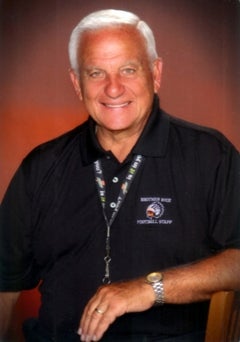

Fracassa begins this season with 416 wins,which is sixth in the nation.

Courtesy photo

In addition, he has won the Duffy Daugherty Memorial Lifetime Achievement Award from his alma mater, Michigan State University.

Once he was offered the backfield coaching position with the NFL Detroit Lions. A couple other times he could have gone back to Michigan State as an assistant coach. He turned down every job offer over the years, laughing, "I'm one of those guys who don't like to leave town."

Though he had a heart double-bypass nine years ago and battles high blood pressure, Fracassa never has missed a game during his career which started in 1960. In February and March of this year he still was rising at 5 a.m. and overseeing agility drills at 6 every day.

Veteran Detroit News sportswriter Tom Markowski has followed his career closely.

Conceding there is some jealousy between public and private schools, Markowski said, "I never get the feeling that there is anything against this guy. He does a lot of things for football in this state. One of the greatest things that Al does ... he'll call up college coaches and say 'Go take a look at (a player from another school).' He does things for kids not in his program because he cares. Al has those connections and cares about people."

One of Fracassa's former players, Jerome Malczewski, is writing two books about him — one about leadership and life lessons and the other more biographical.

Three-sport standoutOne of them will be entitled "Do It Better Than It's Ever Been Done Before." That is a theme he has preached ever since he began coaching. He picked it up from his high school basketball coach, Art Carty, at Detroit Northeastern where he starred in football, basketball and baseball at 5-foot-8 and 160 pounds.

"What makes him special, what's remarkable is not his won-lost record, but his ability to elevate the human spirit," Malczewski said. "He gets so much out of every single player in practice as well as games. He makes every single boy know how important he is. He appreciates the scout team and the third stringers. He tells the team how proud he is of good grades. Once he celebrated a boy who reached Eagle Scout status in front of the team."

The ageless coach, who will turn 81 on Nov. 13, has an uncanny knack of getting his players to buy into a team philosophy.

There is no better example than Steve Stergar, an average athlete who worked himself into a starting tight end role as a senior at

Brother Rice (Bloomfield Hills, Mich.). In the third game he blew out a knee, ending his career. Stergar was a superb student and even before surgery he told the other players that he could still contribute by tutoring anyone who was having academic problems.

Fracassa, whose parents and two older brothers migrated from Italy, grew up in Detroit during the Depression. He would sell newspapers. To help heat the family home he would walk railroad tracks looking for pieces of coal that may have fallen from trains. He also would collect wood and, interestingly, still has a yard filled with wood.

Old habits apparently die hard.

Endless flameHe was not a total saint, however.

One day he and a friend approached a construction site looking for scraps of wood. After being told to leave by a couple workers, they basically tricked a third man to allow them in a back area to grab a few scraps. However, they ended up dismantling the wooden outhouse the workers had constructed and scampered off with a major haul.

Besides earning All-State honors as a quarterback at Northeastern, Fracassa used his arm to once strike out 17 batters in a baseball game. That arm helped him earn a football scholarship to Michigan State where he proved to be a very valuable guy even though he was basically a scout team quarterback, always preparing the varsity for the next game.

Teammate John Matsock once said, "We played such good defense because our scout team quarterback was better than most of the opposing quarterbacks. He was an inspirational guy, tremendous motivator and a heck of a leader."

Fracassa had the misfortune to play behind three consecutive All-American quarterbacks, but he never lost his fire, never missed a day of practice and was loved by his teammates. During his college career, the Spartans won a national championship in 1952 and he was able to make the trip for the 1954 Rose Bowl game. As a senior he received the coveted Fred Danziger Award.

Coach Duffy Daugherty gave him the game ball for a touchdown pass against Texas A&M, but his college career can best be summed up by a late-game appearance during his senior year. The quarterback called his own plays in those days, but two halfbacks and an end all refused to run his play. Fracassa figured out that they were going to force him to run the ball. So he did, scoring himself on a short run and was triumphantly carried off the field on the players' shoulders.

Shades of RudyFracassa wore uniform No. 22 in honor of his favorite player, Bobby Layne, and wanted to be a professional football player. However, he had to settle for coaching and teaching, landing his first head job in 1960 at

Shrine Catholic (Royal Oak, Mich.) as head coach in football and baseball. His football record was 44-19-5.

"I don't think you should be a teacher if you don't care about kids," he said.

Ron Ranieri, who played for Fracassa in his early years at Shrine, said the coached wanted to establish himself in those days.

"We had to crab crawl off the field every time and he'd be right behind us," Ranieri said. "There was no choice. He is a commanding personality. He says he can't do that (coach that way) any more. Pretty much every person who ever played for him if he said to get on a plane to California tomorrow we'd all do it. It's burned into our brains. He's the most influential guy in my life."

Mike Randall, a running back and linebacker at Shrine, more than feels the same way about his former high school coach.

Randall said he entered high school with a chip on his shoulder and easily could have spiraled out of control. Fracassa actually later wrote about Randall, a troubled youth, to help him earn his Master's degree. The paper Fracassa write received an A-minus, though Randall would have give it an A-plus.

"My father died at age 37 of alcoholism when I was a freshman," Randall said. "Al is probably the most influential man in my life. He was the father I never had."

A tough dad to be sure.

Fracassa got fed up with Randall's cockiness one day, the day he challenged his coach to a boxing match. Randall boxed a little, but didn't know Fracassa boxed in the Army.

It wasn't much of a contest.

"A whole bunch of people showed up (for the fight)," Randall said. "It seemed like before I laced on my gloves, he hit me 10 times and I was on the floor. It was kind of the final 'I love you as a father' type thing. If I hadn't played for Al, I don't know if I would have had the strength to believe in myself. My mother worked two shifts. I had no guidance. Fifty years later, if he asked me, I'd run through a brick wall. You don't ever want to let him down."

"He (Randall) was a big kid compared to me," Fracassa said. "He was a smart aleck. I kind of taught him a lesson and he never forgot it."

Two of Randall's sons later played for Fracassa at Brother Rice.

Teaching never stopsFracassa moved on to Brother Rice in 1969 where he has produced a brilliant 372-98-2 record. He also coached baseball for 12 years and won a city championship at the home of the Detroit Tigers.

Mike Coughlin was a member of that first team and it took just one speech at a pep rally to become a believer in his new coach.

"After the first 10 minutes he didn't talk any more about football," Coughlin said. "His expectations were to be good students in class, good sons to our dads and good outside of school. He cared about us not just as football players but as human beings. That has stuck with me for 45 years."

A two-way lineman, Coughlin estimates that he played just three varsity minutes as a senior, but he loves Fracassa so much that he is thrilled to be an assistant statistician for the team today.

"Coach never stops teaching," Coughlin said. "He can say things to a player to motivate him but not embarrass him."

Coughlin estimates that close to 500 admirers — with only word-of-mouth advertising — once attended an appreciation banquet for Fracassa.

"It was quite remarkable," he said. "Player after player got up to the microphone and said what coach had done for them. Then we all pitched in and bought him a new car."

Kevin Hart, now the freshman coach at Brother Rice, played tackle on Fracassa's 1974 team which included 10 Division I players and was the mythical Class A state champion with a 9-0 record. His father, tight end Leon Hart, won the Heisman and Maxwell trophies at Notre Dame and played eight years in the NFL.

In junior high, Hart admitted to being something of a troublemaker. He once slid down a bannister and accidently ran into a nun, Sister Merrietta.

"(She) told me that I needed to go to Brother Rice because their (new) coach was a boxer," Hart said. "As a freshman (at Brother Rice) I was terrified."

Hart said Brother Rice wasn't too creative on offense during his playing days.

"We threw two or three times a game," he said. "It was all wishbone, grind it out. As he got older, he got more innovative. Coaches from all over would call and ask him to talk about the passing game. He became a passing aficionado.

"All we did was run and wear out the opponents. He'd just yell out the plays from the sidelines. He didn't care if they (the opponents) heard it or not. Because of our conditioning, we always thought we were going to win in the fourth quarter.

"He is so humble and knows how to get the most out of every kid. I never left the field (even after being chewed out) feeling rejected. We always could redeem ourselves. He was way ahead of his time."

Today Hart, who had two sons play for Fracassa, hangs out on the sidelines during varsity games.

"He tells me to go get him some water," the freshman coach said. "My wife tells me, 'He still orders you around like one of his kids.' I

am still one of his kids."

Winning titles, making pasta and good genesFracassa is especially proud of his 1977 team, which won a Division I state championship with a 12-0 record.

"We had a lot of termites on that team, kids 142, 150, 160 pounds," he said. "It was a really gratifying year. We didn't have one kid who got a scholarship."

Al and his wife of 57 years, Phyllis, have four children and seven grand children. One of their grandsons, Jason Fracassa, holds several state passing records, but he did it at

Stevenson (Sterling Heights, Mich.).

One of his favorite hobbies for many years was making spaghetti. He estimates that he helped raise around $150,000 for Brother Rice by auctioning off pasta dinners with Al.

He also is somewhat of a hoarder, refusing to dispose of hundreds of game programs he has collected over the years. To keep Phyllis from going completely crazy, he now has a storage locker. When he shops at a discount store such as Costco he can't pass up bulk bargains, always purchasing more than he needs.

When Phyllis says they don't need something, he replies "Well, it's on sale."

What will happen when the "old warhorse" finally hangs up his whistle for good?

Phyllis says, "I think it's going to be kind of traumatic. I'm talking to other women about it."

Several sources have reported that Fracassa has been offered an office at Brother Rice for the next four or five years. He will be a "coach emeritus."

His ability to draw great players to Brother Rice and help players throughout the city receive college scholarships will remain invaluable.

As Mike Randall puts it, "We must continue the Rice tradition. He's like Moses on top of a hill preaching and then he lets everybody else run the program."

Meanwhile, Fracassa eagerly looks forward to the 2013 season opener.

Among the spectators, as always, will be his brothers ages 92, 87 and 84.

"They're very fond of their little brother," he says. "It's been a wonderful career and I hope we have a good year."